The top selling video game of all time, at 170 million sales, is Tetris. First released in 1984, Tetris is one of the oldest video games. But unlike Pong, or Super Mario Bros., or any pretty much other game from that era, Tetris is still widely played and enjoyed today1. Tetris 99, a "battle royale" edition of Tetris, was released on February 13, 2019 and is already massively popular. Its mechanics are almost identical to those of the original game. Isn't that kind of weird? Video games were still a brand new concept when Tetris was created. What's so special about Tetris that keeps it popular 35 years later?

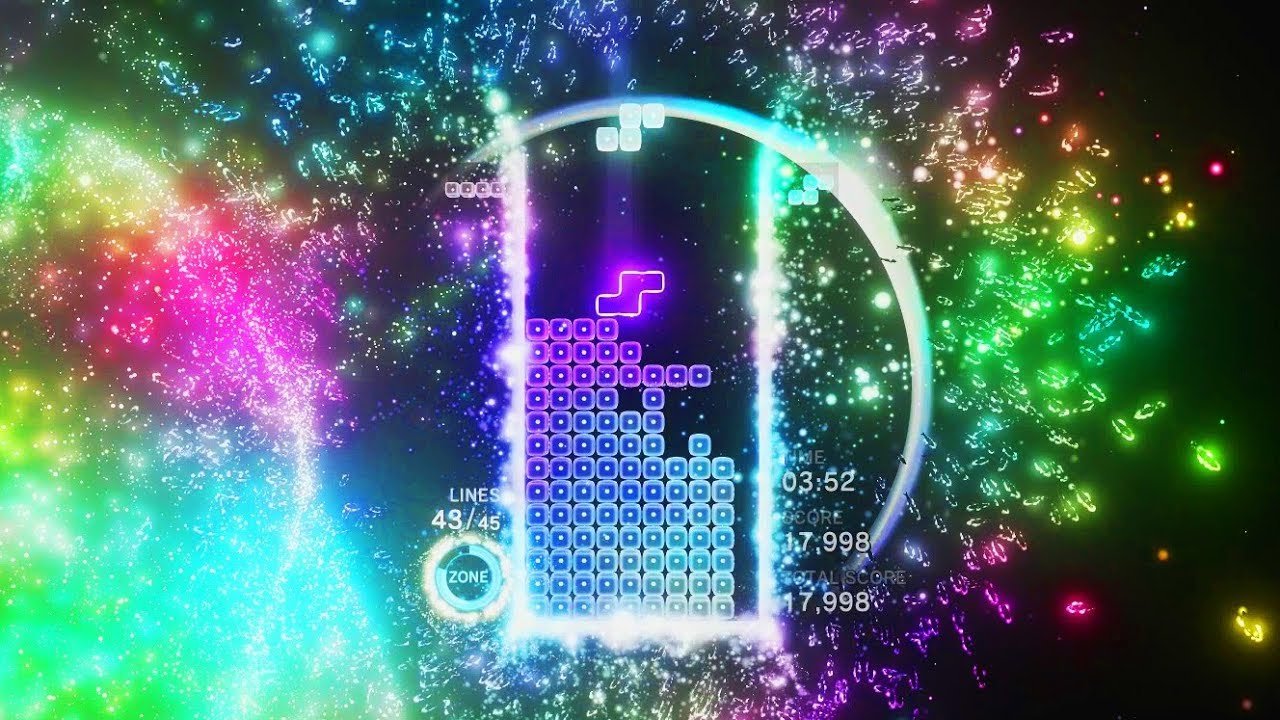

Tetris Effect (2018)

History

Tetris was first released in 1984 in Soviet Russia. Because everyone who played it liked it so much, it made its way around the world and ended up in the U.S. in 1987. An agreement with Nintendo led to Tetris being bundled with the GameBoy, their new portable gaming console, in 1989. The GameBoy was a massive success, thanks in large part to how fun Tetris was.

Over the years since, iterations have led to small lasting changes to Tetris' design. The GameBoy version added multiplayer, letting players race against their friends on separate boards. Other games introduced the ability to hold a piece and see a preview of where the currently falling piece will land. But... that's pretty much it. Anyone who played the original Tetris could pick up Tetris 99 and understand what's going on.

Compare this to games like Super Mario Bros. In 2017, Super Mario Odyssey was released as the latest installment in the Mario franchise. But aside from very loose concepts like "running" and "jumping", it is almost completely unlike the original 1985 platformer. If a seasoned Super Mario Bros. player traveled forward in time to today, they would have no idea how to even control the new game. 2D platformers, such as New Super Mario Bros. U Deluxe, are much more similar to their predecessor. But those are often criticized for being derivative and uninteresting. Tetris, in comparison, held up much better.

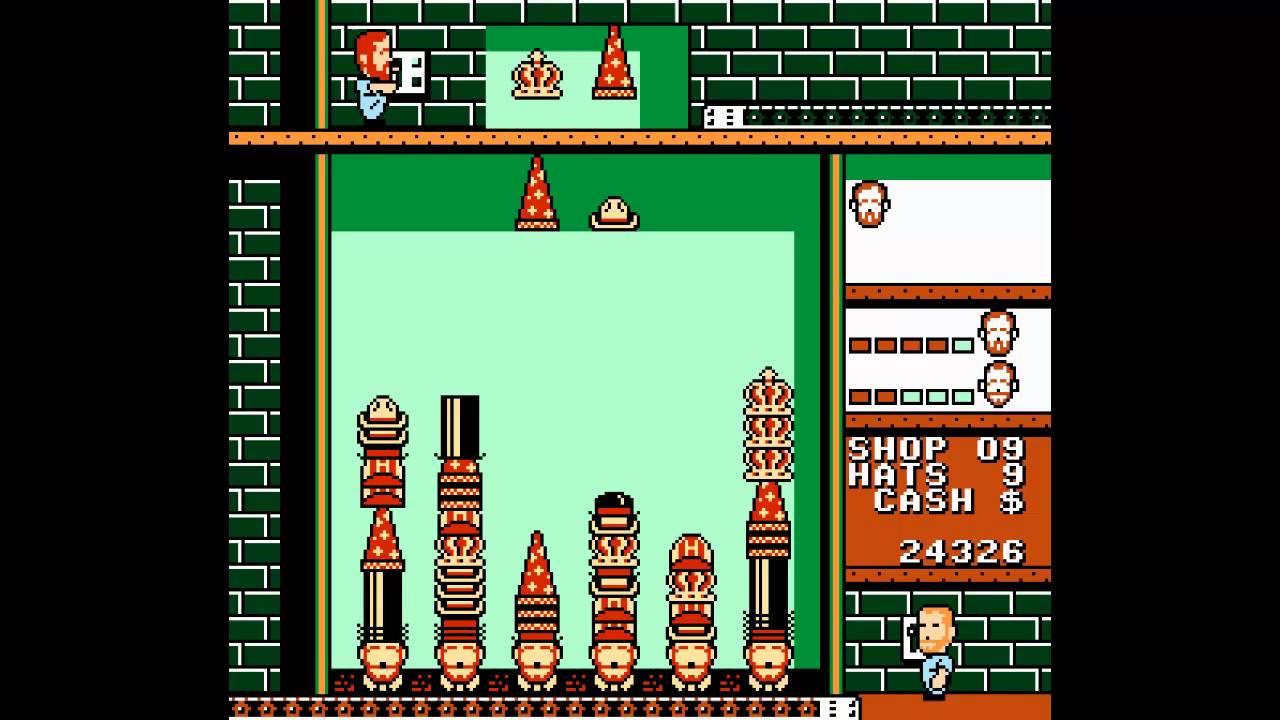

It's not that people didn't try to make new versions of Tetris. In the early 1990s, many variations were released that significantly changed the basic gameplay. Hatris, for example, involved stacking pairs of hats to create matching towers. Welltris changed the playing board from one plane to five. Tetris 2 was about matching colors together. But none of these major changes stuck. They all moved further away from the apparently perfect core of the Tetris experience. So what is that perfect core?

Perhaps the least successful hat-based game in history

Gameplay

The center of any game experience is the game loop, and in Tetris, it's especially obvious. As soon as you start, you control a single colorful piece. But wait, you can't totally control it- it's falling down, with no way to stop! You shift and rotate it into a good position, then settle it safely on the bottom of the board. But- oh no- now you have another one! At the simplest, lowest level of Tetris is a clear cycle of building and releasing tension. The inevitable fall and brief pause of each tetromino is a switch between danger and safety.

At a slightly higher level, there's clearing the lines. This is another tension-release cycle. You have to get closer to danger- building up the stack- to clear a line and become safe again. This happens over and over again, the constant flow of pieces always hooking you back into the loop, giving you just long enough to take a breath before pulling you back in with another piece.

Tetris is also very intuitive. The oddly-shaped pieces fit together like kids' building blocks. The natural thing to do is try to put them together, and when you do, you get a satisfying noise and the blocks flicker out of existence, dropping everything below them. Now you understand the game- keep the pieces from piling up by fitting them together into lines. And if you don't get that right away, the game will teach you through failure. If left alone, the game will play itself, constructing an ugly, jagged tower that shoots right to the top of the screen, at which point you get a GAME OVER. That's no good! Either way, the game explains its simple concept through gameplay. It's not surprising that it was able to cross the language barrier so easily.

This intuitiveness gives it a low skill floor. Anyone, kid or adult, can pick up Tetris and play right away. The game is easy to understand at a glance, fitting all on one screen. You can learn by watching someone else play, or just by mashing buttons randomly to see what happens. No in-depth knowledge of game conventions is needed. Tetris' potential audience is pretty much everyone.

Crossing the generation gap

But it also has a high skill ceiling. Mastering Tetris isn't as simple as figuring out the dominant strategy and having decent reflexes. Small features like "hard dropping" (pressing down to immediately send the current piece to the bottom of the board, rather than waiting for it to fall") and awarding higher scores for trickier line-clearing techniques (such as clearing three lines at once with a rotated T block) allow players to keep getting better. And what better motivation for improvement could there be than competition?

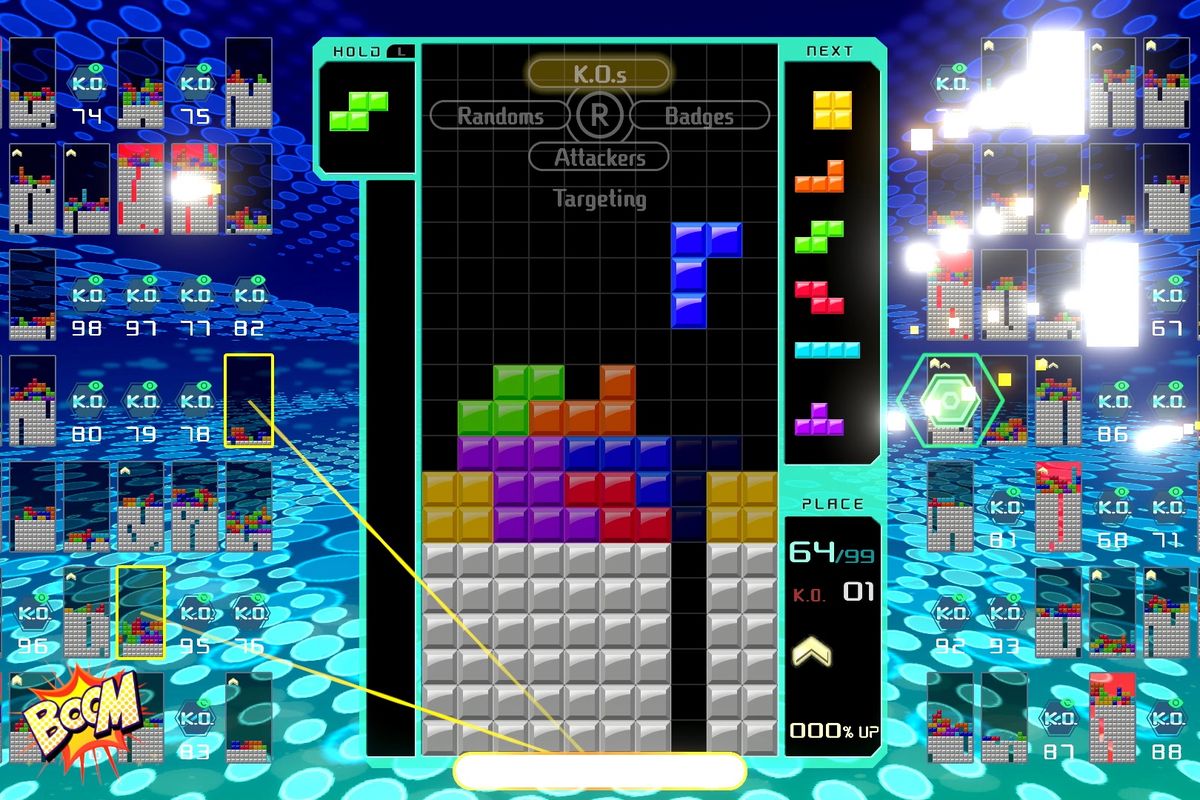

Multiplayer, introduced in the 1989 GameBoy version, lets you compete in Tetris against your friends. Now speed and score are important, because if you're slow, your opponent will clear a row before you. If this happens, it'll mess you up with rows of garbage blocks that push your stack up further. But you can retaliate by clearing lines of your own and sending garbage over to them. This back-and-forth constantly pushes you to improve, fighting against both the game and your opponent's own skill. Modern competitive games like Tetris 99 and Puyo Puyo Tetris successfully build on this feeling to create a progression-based experience where players are constantly pushed to become better.

You don't even have to compete against other Tetris players

Mechanical + mental skill

Tetris also gives a balanced workout for your hands and brain. Part of the game is quick, twitchy action- rotating the pieces, dropping them down when they're in position, slipping them into tight spaces. The other part is strategy- figuring out where to put the pieces and how to construct your board in order to optimize your play.

On the mechanical side, there are different levels of skill. The basic level is moving and rotating the pieces to line up how you want. There is plenty of time for this, so it's pretty forgiving. But at a high level- say, when competing with someone- hard dropping comes into play. Now it's a fast-paced game of shifting and spinning the pieces in as little time as possible, at which point you slam them into the bottom of the board. Misdrops, where the player knew where they wanted the piece to go but messed up the movement for it slightly, are common at high levels of play.

Similarly, there are different levels of mental skill. The basic one is short-term, where you look at a piece and decide where it could go. A T-shaped piece shouldn't go T-side down on a flat board, for example, since it would make the lower line harder to fill up. But in the long term, skilled players will think about how to set up optimal scoring opportunities. Sometimes they will avoid clearing a line right away to set up a powerful multi-line simultaneous clear (for example, by dropping a line piece into a 4-tall gap of otherwise complete lines). And just like in strategy games such as chess, advanced players will use complex tactics such as "T-spin doubles" or "four-widing" to get the most out of their pieces.

Conclusion

Looking at these, it's pretty clear: Tetris does a lot of the fundamentals really well. It has a strong and intuitive core loop, opportunities for mastery and competition, and a balance of mental and mechanical skill. While there have been additions to it over the years, attempts to change Tetris' basics have largely failed, losing some of the essential properties that make it great. Tetris remains popular because it does so well on so many basic aspects of game design.

Or maybe it's because the theme music absolutely slaps.